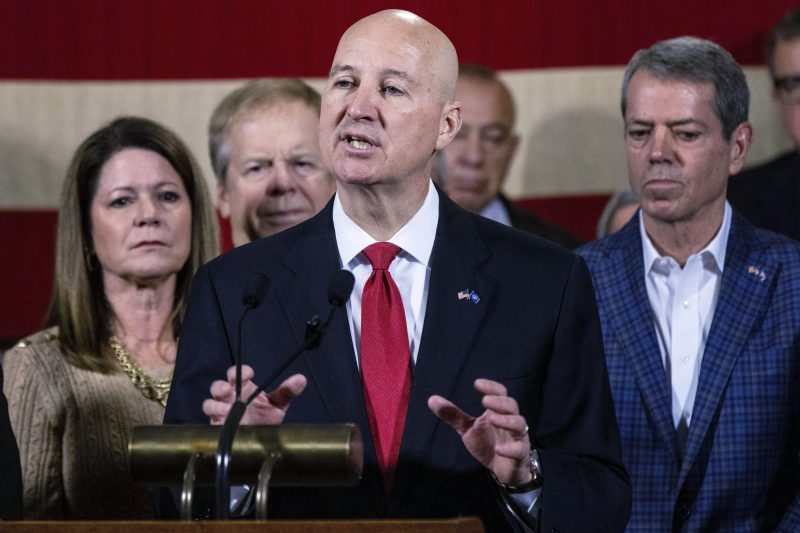

Before Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen (R) made the announcement Thursday that he would appoint former governor Pete Ricketts (R) to the Senate, Pillen made a point of pitching his pick as politically pragmatic. He said he didn’t want a “placeholder” for former senator Ben Sasse’s (R-Neb.) seat, and he emphasized choosing someone with the strength to hold the seat for many years to come.

The announcement Thursday scans as unsurprising: Ricketts is the most established figure in the Nebraska GOP and supported Pillen as his successor to the governor’s mansion. But the argument about Ricketts’s political strength would have seemed utterly crazy less than two decades ago.

It goes to show how dramatically things can change in politics: With this appointment, Ricketts has now completed one of the most remarkable comebacks from a losing Senate campaign in modern American history.

Ricketts made his first run for office in 2006, and it went exceedingly poorly. Despite Republicans targeting a Democratic senator in a red state and having high hopes for the former Ameritrade executive as a chosen challenger, he lost to Sen. Ben Nelson (D-Neb.) by a whopping 64 to 36 percent.

Ricketts spent roughly $14 million of his own fortune on a 28-point loss. As a Republican in Nebraska. And against a first-term senator who had only narrowly won office six years earlier.

It’s one of the biggest losses on record for a candidate who would later join the Senate. Many senators have previous losses under their belts, but almost never have they been as lopsided as Ricketts’s.

A number of senators have lost extremely close Senate campaigns before joining the upper chamber. Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) lost by 524 votes in 2002. Former senator John Ensign (R-Nev.) lost by 428 votes in 1998. Former Senate majority leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.) lost by fewer than 700 votes in 1974.

Others have come back from slightly larger but still competitive losses, including Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.), Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) and former senator Gordon Smith (R-Ore.).

But even when they lose by more lopsided margins, they generally at least hit a number that starts with four. Former senator Barbara A. Mikulski (D-Md.) took 43 percent in a 1974 campaign before winning her seat in 1986. George Voinovich (R-Ohio) took 42 percent in 1988. Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) took 42 percent in 1962. Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) took 41 percent in a 1994 Senate campaign (though in blue Massachusetts).

And now-Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine (R) took 42 percent in 1992 before winning a Senate seat two years later. (Remarkably, DeWine was elected to the Senate by double digits in 1994 and then lost reelection by double digits, taking just 44 percent of the vote in 2006 — the same year Ricketts lost — before making another comeback and becoming an extremely popular governor today.)

Incidentally, one of the biggest losses we could find for a candidate who would later become a senator came from the man Ricketts lost to in 2006: Ben Nelson. He took just 41.7 percent of the vote in his 1996 campaign, before winning his seat in 2000 and then embarrassing Ricketts six years later. But that 1996 figure is still nearly six points better than Ricketts did in his own loss.

There have been larger losses, but they come with asterisks. Now-Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) was actually stuck in the single digits in his first two runs for the Senate in 1972 and 1974, but that was as a little-known political novice running under the banner of the “Liberty Union” party. And now-Sen John Kennedy (R-La.) took just 15 percent in a 2004 Senate campaign, when he was a Democrat, but in a race that featured multiple Democrats splitting the vote.

Of course, we’ve known for a while that Ricketts’s career was going places. After winning a very tight gubernatorial primary in 2014, he won the general election both then and in 2018 by 18 points. So Pillen is right that he’s now a proven political commodity who should have little trouble winning the seat in his own right.

Ricketts hasn’t done that yet, unlike the others mentioned above, but he in all likelihood will in 2024. And if and when he does, he’ll register one of the biggest reversals in modern political history for a failed Senate candidate.