MLB payrolls: Did Dodgers, Yankees buy their way into World Series?

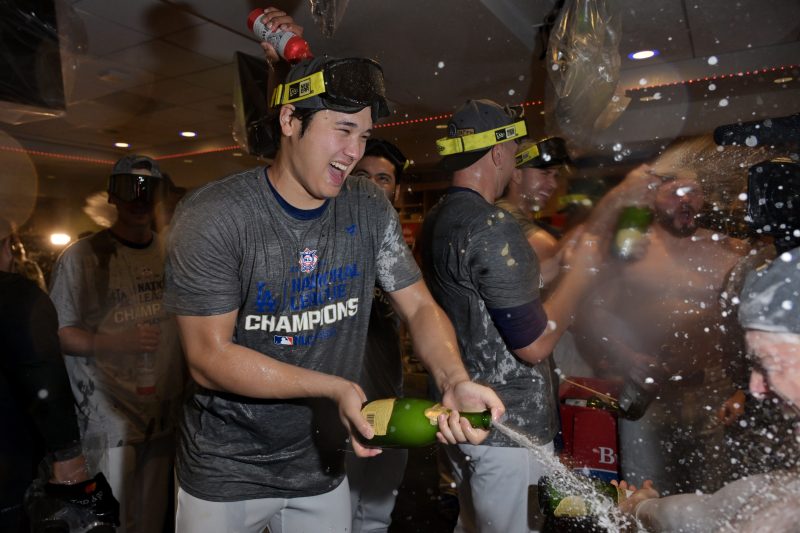

This New York Yankees-Los Angeles Dodgers World Series has generated a significant amount of excitement. The two iconic franchises have not met in the Fall Classic since 1981, and plenty of big-name stars like Aaron Judge, Juan Soto, Shohei Ohtani and Mookie Betts add sizzle to the proceedings.

Yet for fans of middle-class Major League Baseball clubs, who don’t enjoy the large payrolls of these coastal elites, the World Series might prove a dispiriting point: That championships can be bought, that their efforts to compete are futile when faced with the big boys’ big bucks.

With that, USA TODAY Sports takes a look at the dollars and sense of this 120th World Series

Do the Yankees and Dodgers have the two highest payrolls?

Not exactly. There are various methods to calculate payroll, and myriad sources to cite, but the undisputed No. 1 by any methodology are the New York Mets.

Follow every MLB game: Latest MLB scores, stats, schedules and standings.

Steve Cohen’s team was a significant disappointment for much of the season, until catching fire in mid-summer and making it all the way to Game 6 of the National League Championship Series. You might say he finally got what he paid for: The Mets ranked No. 1 in preseason payroll ($305.6 million, per USA TODAY Sports), end-of-season allocations ($317.7 million, per Spotrac) and projected competitive balance tax payroll ($356.2 million, per Cot’s Baseball Contracts).

A large chunk of the Mets’ expenditures is dead money, with the club covering more than $50 million of salary for pitchers Justin Verlander and Max Scherzer, both traded in 2023.

Yet the Yankees and Dodgers are right behind: The Yankees were No. 2 preseason ($303.3 million) and the Dodgers No. 3 ($249.8 million), while they flipped spots for the luxury tax – or CBT – payroll, the Dodgers at $351.7 million, the Yankees at $314.8 million, per Cots.

Is Shohei Ohtani the highest-paid player in the game?

Yes – kind of. His 10-year, $700 million contract easily sets records for both total value and average annual value. Yet the contract is so heavily deferred – Ohtani receives $2 million per season and will be paid $68 million annually from 2034 to 2043 – that the present-day value is far less. It’s calculated at $28 million for current payroll purposes and $46 million for CBT payroll.

But Ohtani will certainly enjoy a comfortable retirement – and as an international superstar, earns well north of $50 million annually in endorsement income.

Does that make Aaron Judge the highest-paid player in 2024?

Just about. His nine-year, $360 million contract pays him an even $40 million per year. In 2024, that was a tad less than Verlander and Scherzer, who made $43.3 million. And next year, it will be just shy of Philadelphia ace Zack Wheeler’s $42 million as he begins a three-year, $126 million extension.

Judge’s salary was also matched by Texas right-hander Jacob deGrom, who made $40 million this year and also in 2025, before dropping down to $38 million in ’26. While ace pitchers are in such rare supply that Judge’s single-year salary might get superseded, his average annual value stays right at the top.

For now.

Will Juan Soto make more than Aaron Judge?

Almost certainly, which seems mildly blasphemous given Judge’s two MVPs to Soto’s none. Yet Judge was 30 when he re-signed with the Yankees coming off an MVP season in 2022.

Soto is just 25 – he turns 26 on Friday, Game 1 of the World Series – and has maintained a largely MVP-caliber level of production since he was 20 and leading the Washington Nationals to the 2019 World Series title.

Soto made $31 million this season in his final year of arbitration eligibility. Once he hits the open market – with the Yankees still a decent bet to re-sign him – he will likely land a guarantee north of $500 million.

In other words, somewhere between Judge and Ohtani.

How many $100 million men do the Dodgers and Yankees have?

If there’s one thing that separates high-revenue teams from others, it’s the willingness to throw around a nine-figure contract and believe it won’t sink you should it go awry.

The best teams are both aggressive and wise in such expenditures, and the Yankees and Dodgers, with four and six nine-figure stars, respectively, are no different.

As such, the Yankees and Dodgers’ massive investments greatly impacted their seasons and into the playoffs:

Judge (nine years, $360 million): 58 regular season home runs with a 1.159 OPS.

Giancarlo Stanton (13 years, $325 million, with Marlins paying $30 million): Four homers, 1.222 OPS this postseason.

Gerrit Cole (nine years, $324 million): Yankees are 3-0 in his postseason starts after reigning Cy Young winner’s season delayed by elbow injury.

Carlos Rodón (six years, $162 million): Started and won Game 1 of ALCS and also started clinching Game 5.

Ohtani (10 years, $700 million): The first 50-50 season in major league history, and a .934 OPS and 11 RBIs in 11 playoff games.

Betts (12 years, $365 million): .863 OPS in season shortened by hand injury, but a .296/.404/.659 line with four homers this postseason.

Yoshinobu Yamamoto (12 years, $325 million): 3.00 ERA in 18 starts, five shutout innings in NLCS Game 5.

Freddie Freeman (six years, $162 million): 22 homers, .854 OPS, but slowed by ankle injury in playoffs.

Will Smith (10 years, $140 million): 20 homers, 116 adjusted OPS, key homer in NLCS Game 6.

Tyler Glasnow (five years, $136 million): 3.49 ERA in 22 starts before elbow sprain shut him down.

So, do the Yankees and Dodgers buy all their players?

Eh, not really. Of the 26 players on the Dodgers’ NLCS roster, seven were fully homegrown – drafted or signed and developed. Seven more were acquired in trade, largely using homegrown minor league assets. And four others – three members of their stout bullpen and slugger Max Muncy – were waiver claims.

Four of their eight free agent acquisitions – old friend Kiké Hernández and relievers Ryan Brasier, Blake Treinen and Daniel Hudson – were hardly of the big-bucks variety.

The Yankees? Six homegrown players including three big ones: Judge, shortstop Anthony Volpe and starter Clarke Schmidt. Four were acquired through waivers and six via free agency but the bulk of the roster – 11 in all – came via trade.

Many of those deals did involve flexing financial might, such as acquiring Stanton and the $265 million obligation that came from Miami with the slugger. A strong package of major league-ready players landed Soto and his $30.1 million due via arbitration. Yet there’s plenty of savvy in there, too – most notably rookie starter, Luis Gil, acquired from Minnesota for Jake Cave.

In short, there’s plenty of ways to dial up a championship roster. But a loose checkbook doesn’t hurt.

With money so key, do the same teams always win the World Series?

Not at all. In the 23 seasons since the Yankees were the last team to repeat as World Series winners – claiming three consecutive championships and four in five years from 1996-2000 – 16 franchises have won the Fall Classic.

The Boston Red Sox won four titles (2004, 2007, 2013, 2018) in that span, the San Francisco Giants three (2010, 2012, 2014) and the Houston Astros (2017, 2022) and St. Louis Cardinals (2006, 2011) two each. The rest? A true mélange, from mid-market Kansas City to big bad Philly and quite stunningly, two teams from Chicago – the famously cursed Cubs and the White Sox, who broke up decades of ineptitude with a 2005 championship.

Do fans prefer watching World Series involving lower-payroll teams?

Not really. The 2023 World Series, pitting the Arizona Diamondbacks (21st in payroll) against the Texas Rangers, who had a top 10 payroll but had never won a championship in franchise history, was the lowest-rated Fall Classic in history.

So why all the griping?

Good question. And there’s a pretty good chance those swearing off this big-bucks battle will find themselves sneaking a peek at it all. Those TV ratings aren’t gonna show up by magic.

The USA TODAY app gets you to the heart of the news — fast. Download for award-winning coverage, crosswords, audio storytelling, the eNewspaper and more.