There’s too much pressure on these kids: Let’s make the LLWS more fun

We love to celebrate our kids. For a week or two at the end of each summer, we adopt someone else’s.

We follow their every move from a small ballpark in central Pennsylvania, or from the television screens in our living rooms.

We watch them make spectacular plays in the field and hit the ball over the fence. We hang on their emotions, too: Their deep breaths, their clenched faces, their triumphant leaps into coaches’ arms.

Why are we so fascinated by the Little League World Series? Because it thrusts everyday life into the national spotlight. Many of us have been part of teams that have tried to get to Williamsport, or we just used to hop into the “way” back of our coach’s station wagon on the way to the diamond.

Most of us never got to play on national TV in front of millions of viewers, with broadcasters who normally call major league games detailing our actions. These kids’ dreams become ours. Maybe we even forget, at least momentarily, they are kids.

We expect them to come through and we cheer like heck when they do.

But what about when they don’t?

They are sometimes in tears, too, as are their parents, during and after the most excruciating moments.

“I promised myself that every minute of these games I was gonna enjoy it,” Michelle Anderson, whose son Chase plays for the Lake Mary, Florida, team and husband Jonathan manages, told ESPN this week. “I was a stress ball to get here, but once we got here I said, ‘You know what, I’m going to enjoy the moment.’ ”

It’s a moment where kids’ games are broadcast to the world and their coaches are miked up.

With all the scrutiny, sometimes it’s difficult to decipher the purpose of the event. While it’s tempting to look at the Little League World Series a showcase of the most talented 12-year-old baseball players, it’s purpose is much more simple: It’s once-in-a-lifetime event for kids (and their parents) fortunate enough to soak up and experience it.

We love the Little League World Series, but there are subtle ways to make it even better. Here’s how we can reduce the pressure on kids who play in it and open up opportunities for more of them to have a shot at it.

Keep the broadcasting light

That should have been a double play. Easily.

You want to throw something a little better than that.

That ball could have been caught. Sometimes you give up just split second too early.

Those are on-air comments from ESPN’s Karl Ravech and Todd Frazier in a game leading up to Saturday’s United States championship, which featured Boerne, Texas, and Lake Mary, Florida. Florida plays for the championship Sunday against Chinese Taipei.

We have a tendency to connect the Little League World Series with the majors. Maybe it’s because 64 confirmed “graduates” of the LLWS have played in the big leagues. But that’s 64 players since 1954.

One of those players is Frazier, who went 4-for-4 in the championship game to help his Toms River, New Jersey, defeat Japan in 1998.

Frazier played an 11-year major league career. Now 38, he coaches his son’s baseball team. His broadcasting style is tough and supportive.

“That was a perfect executed bunt,” he said when Hawaii’s Kolten Magno sacrificed a runner to second base during a tense elimination game with Florida this week. “Only thing better, (if) he would have gotten it down more to third base … that would have been a knock.”

Magno also singled to start a four-run, third-inning rally to tie the score 4-4. Florida’s lead began to evaporate when two of its players couldn’t turn either end of a double play. The Florida shortstop bobbled the ball and recovered, but the second baseman was looking at first when he received the throw and dropped it.

“And everybody’s safe!” Ravech said.

The scene ramped up, as everything connected to youth sports seems to do. Hawaii parents loudly cheered after the mishap.

“Once the bobble happens, understand: Gotta get that first out,” Frazier said during a replay.

He spoke in a animated voice that helped capture the drama of the moment. But part of the drama was on the shortstop’s face. It wasn’t a dismissive look you might see on a major leaguer when he makes an error, but a look of distress.

It’s a look that can be soothed in the privacy of a dugout or well after the game by a coach’s encouraging words. Had the words come from Frazier, a big leaguer as recently as 2021, the kid would have heard them on the replays of the clip.

“You can see he took his eyes off the ball,” Frazier might have said. “Tough play those guys are capable of making.”

He and Ravech struck a more age-appropriate tone the day before when Florida played Staten Island, New York. It was a familiar scene if you’re a baseball parent. Jessica Mendoza, a major league broadcaster who is also a Little League mom, was also in the booth. She noted how Staten Island coach Bob Laterza constantly chatters with his players while they’re playing.

“He yells all game long,” she said.

At one point, Laterza called timeout and gave one of his hitters an earful of information in between pitches. The kid looked straight ahead and nodded as his coach spoke, perhaps more confused than when he stepped out of the batter’s box.

“Was he listening to him?” Ravech said.

“I think he was,” Frazier said. “For sure. Can’t remember everything.”

Coach Steve: Some parents need to rethink how they talk to their child athletes

Have more Julie Foudy moments

What question will ESPN reporter Julie Foudy ask next?

“How did you get your kid to eat eggplant?” she said to Jana Grippo, mom to Stephen, a left-handed pitcher for Staten Island.

“In my house, we have a rule: You’ve gotta try it before you say you don’t like it,” the mother replied.

Foudy has found ways to distract kids from the big stage. She played pickleball as a partner of Florida’s Liam Morrisey while asking about his care for his flowing dark hair (shower, brush, conditioner, blow dry). She challenged Henderson, Nevada’s Gunnar Gaudin to solve a Rubik’s cube in under 39 seconds while she chatted with him and teammate Wyatt Erickson about their squad. (He did it in 36 seconds.)

She talks to parents while their kids are in the act of playing, often pitching or hitting, a humorous exercise even without her commentary.

“Rule No. 1 is watching your son,” she told Texas parent Dru and Jessica Steubing as they looked away from her and at the field. ‘But I will ask the questions and put the mike in your face.’

In the middle of one about the low-salt sunflower seeds the couple makes, they shot up and gave their complete attention to a ball their son Gage put into play. They jumped and cheered as it dropped in for a hit.

“Yes! I love when that happens,” Foudy said.

Her words poked fun at the ebbs and flows of our emotions when we watch our kids play sports. It also reminded us not to take those sports (or ourselves) too seriously.

Be more selective in miking up coaches

During a Nevada-Texas game this week, Nevada’s catcher fielded a bunt with a runner on first and errantly threw the ball to second base. The kid immediately knew he made a mistake (as most 12-year-olds do), and you could see him crying through his catcher’s mask.

“We gotta get that out at first, man,” Nevada manager Adam Johnson told his catcher during a miked mound visit a few moments later. The kid started crying again.

Johnson caught himself, like we all do sometimes as coaches when we say something that’s slightly off. Usually, we have the privacy of our team correct ourselves.

Johnson tapped the catcher’s helmet.

“Forget about it, though,” he said. “You’re all right.”

It was a one of those personal instances a coach should be allowed to have with his young players without everyone watching.

This one certainly captured the dramatics ESPN seeks in miking up coaches. But it also caught one unintentionally making one of his players cry.

The network could be more selective in miking up coaches. Record them and then choose the ones that capture them empowering their kids.

For example, the one of Johnson, the assistant equipment manager for the Las Vegas Raiders, speaking to his team before an elimination game with Florida showed us how he inspiring he could be:

“Enjoy the moment and understand what’s at stake,” he said in a calm yet firm voice. “You guys like playing together. You got two more chances you win tonight. Have fun. Smile on your face. Enjoy the moment.”

Play every kid as much as possible

All teams are required to bat their full 12-to-14-man rosters during the Little League World Series. However, they don’t have play everyone in the field.

This rule allows us to see teams’ top fielders who generate those plays we see on SportsCenter. And it gives everyone a better chance to win. It also means a kid could potentially go entire tournament without getting an inning on field at Lamade Stadium.

We all want to win, but isn’t it more important to give every kid a chance to fully experience the Little League World Series? This responsibility falls on coaches as much as Little League’s governing body, which did away with defensive requirements in part due to logistical headaches and violations (intentional and unintentional) of the rules.

Maybe the organization can continue to have discussions to make an equitable format for field play work. In the meantime, coaches can strive to play everyone as as much as possible. That’s the spirit of Little League at the local level.

Requiring their coaches to play everyone more equally in the postseason tournament might also open up an easier path to the World Series. Teams that have a few large, dominant players (height can be a huge advantage at age 12) can ride them all the way to Williamsport. But more teams have a shot if everyone is forced to lean heavily on their entire roster.

Coach Steve: 70% of kids drop out of youth sports by age 13. Why?

Let’s all remember these are 12-year-olds, and they are all about teamwork

Relying on more players also builds team unity. We all need that kind of support.

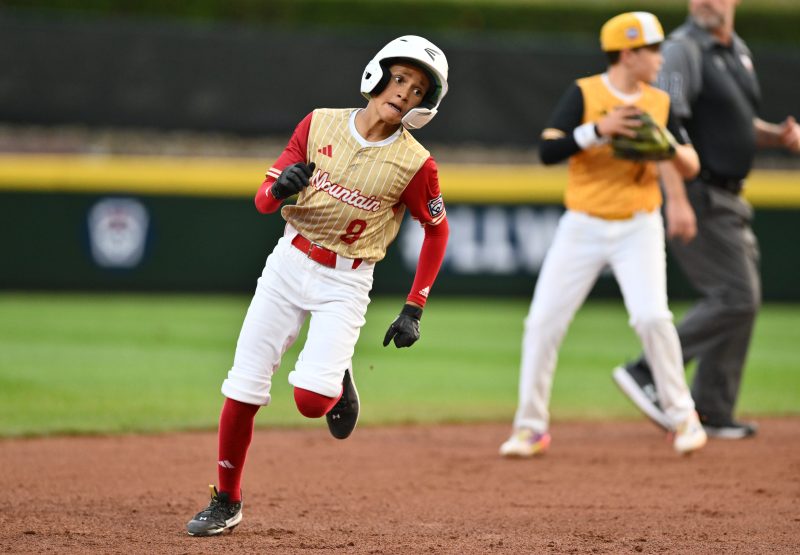

Caleb Gomez is a speedy center fielder on the Nevada team that was eliminated by Florida this week. During that game, Foudy spoke with his mother, Anjanette, about how he and some kids he knows had mental struggles when they played baseball and in school.

You know how you feel as a kid when you strike out or miss a play.

“There is really no safe space to talk about it,” Anjanette told Foudy.

Anjanette, a psychiatric case worker finishing up her master’s degree in social work, helped them start the “Pass the ball” podcast to give young athletes that place. They have recorded three episodes and welcome you to follow and reach out to them on Instagram (@cgogo9) if your young athlete wants to join the discussion.

Caleb came to bat with two outs and a runner on base in the bottom of the last inning. His team was trailing 6-3. With the nerves and pain visible in his face, he lined a hard, two-strike single to left field. He was crying when he reached first base.

Ravech hit just the right note.

“Atta boy, Caleb,” he said. “Man, you got the big hit. So good. Shows how much it means to these kids.”

Let’s hope we see Caleb playing again on TV someday. In the meantime, he gets to go home and be one again.

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.