That doesn’t mean, though, that every ballplayer fits snugly into the Los Angeles Dodgers’ blueprint.

It is a ruthlessly impatient operation, where a championship is the only acceptable conclusion by year’s end as a high-priced mélange of free agents buttressed by elite prospects aims for the game’s apex.

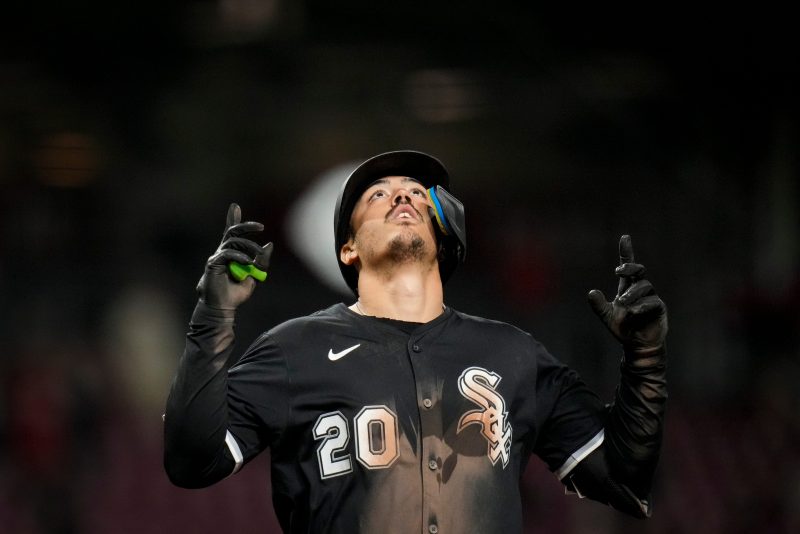

He spent seven years in the Dodger organization, playing sporadically in 129 big league games over three seasons before the inevitable transition from prospect to asset, and hardball heaven to record-setting baseball hell: Traded last July in a three-way deal to the 121-loss Chicago White Sox, a swap that netted L.A. postseason heroes Tommy Edman and reliever Michael Kopech.

Vargas produced 0.0 WAR in his L.A. tenure but did not come away empty-handed; he should receive a World Series ring when the White Sox visit L.A. in a month and retains friendships with countless players and staff in the organization, most notably Mookie Betts and Andy Pages.

And while Vargas produced perhaps the two least productive months by a big-league regular after his trade to White Sox, he’s found so much more: A runway to succeed, a devastating swing and a tight group of young players with which to grow.

Vargas knows that was probably never possible in L.A., a fact he greets pragmatically.

“Every baseball player needs a little bit of time to show up in the major leagues,” Vargas tells USA TODAY Sports. “Some of them, it’s now, they go out there and show it right away. Other guys, they need some time, learning the game, knowing how it’s played.

“When you’re on a team that doesn’t have time for that type of stuff, it’s hard to grow and be better.”

And perhaps Vargas had to journey to the bottom in order to find himself.

‘Anything can happen’

It wasn’t just that Vargas dropped 44 games in the standings when on July 29 he was dealt from the 63-44 Dodgers to the 27-81 White Sox. Nor that the White Sox’s woes were only just beginning, as they lost 39 of 53 games once Vargas joined them to set a modern major league record with 121 losses.

No, it could be argued, for the final two months Vargas might have been the worst hitter on the worst team in history.

He had 14 hits in 135 at-bats, striking out 41 times to just 17 walks, with a .104/.217/.170 line and a 13 adjusted OPS. The bad times spilled into this season, when the White Sox – still on a subterranean floor of their rebuild – rolled Vargas out at third base and saw him produce 11 hits in 79 at-bats, a .139/.236/.203 line over his first 22 games.

If you’re into math, that’s a 25-for-214 sample stretching across two seasons.

At that point, it would be easy to posit that a 25-year-old slugger who once cracked the top 30 of baseball’s greatest prospects was simply suspect. A miss in an industry filled with them.

But back to that onramp.

White Sox coaches continued working with Vargas and, in a fateful meeting in Minnesota, convinced him to make a relatively minor mechanical fix: He held his hands higher in his set-up, aiming to leave himself less vulnerable to fastballs in the middle and upper thirds of the strike zone.

It sounds like granular mechanical minutiae, but it’s now been five weeks since that fateful summit meeting with hitting coaches in Minnesota, and Vargas remains unlocked: He’s on a 38-for-121 tear, with eight homers, a .371 OBP and .904 OPS in his last 32 games.

Sure, that’s not quite 20% of a season, and pitchers will undoubtedly adjust, forcing Vargas to maneuver like he does in one of his many clubhouse games of chess. Yet it also represents the most sustained stretch of production for a prospect who might just reattach the ‘vaunted’ tag in front of his name.

‘It worked right away, and I trusted it,’ says Vargas. ‘That’s all a hitter needs, is having that confidence. You can do some damage when you have that mindset.

‘Anything can happen.’

Including inserting yourself a bit more firmly into a team’s plans. The White Sox optioned longtime first baseman Andrew Vaughn – mired in a .189/.218/.314 funk – to Class AAA on May 23, and Vargas has split time between both corner infield positions.

‘He’s always been a confident guy. I think he understands he’s a good player and sees the game in an advanced way,’ says Will Venable, the White Sox’s first-year manager. ‘Now, after he made that adjustment, he’s impacting the baseball how he’s envisioned it.

‘He’s going into every game with all the tools and abilities he always believed he had and going out and playing great baseball.’

Vargas’s promising, non-guaranteed – but certainly sunnier – outlook mirrors the White Sox at large.

This must be the place

The clubhouse felt almost every one of last year’s 121 losses hard, a campaign that saw manager Pedro Grifol get fired and spare parts like Kopech and starter Erick Fedde spun to other teams.

That’s the environment Vargas found himself in when the White Sox penciled – more like etched – his name in the lineup. Great opportunity, but also a lot to take on for a guy who never got more than 94 at-bats in a single month during his stint with the Dodgers.

‘I think I put a lot of pressure on myself,’ says Vargas. ‘I have way more expectations than what I did here last year.

‘I was trying to navigate my way up. And I was a little bit frustrated.’

Even the greatest players – see Juan Soto – can take a minute adjusting to new environs. It’s even more a whirlwind when the only organization you’ve known casts you aside.

‘It’s hard when you get traded. Especially the first time,’ says White Sox assistant general manager Josh Barfield. ‘You’re used to an organization, you’re familiar with everybody, the surroundings, the coaches and players. There’s comfort in that.

‘When you’re the headliner in a trade, not only do you have to get used to a new league, a new environment, but you’re also trying to prove to everybody that you were worth the trade. Prove it to the fan base. It adds a lot of pressure.

‘At the time he came over he wasn’t getting to play a lot, and probably didn’t have the feel and confidence he has now. When a guy comes over, it’s hard to know what’s real and what just takes time.’

Or perhaps a bit of home cooking.

Vargas did not necessarily set significant physical or developmental benchmarks for the offseason after his initial two-month White Sox stint. He needed home, more than anything, and so he returned to his Miami base, where his mother and father, along with his brother, grandmother, aunts, uncles and cousins awaited.

At one point, 12 people filled Casa de Vargas this winter, a balm for a ballplayer needing a mental reset. Vargas and his father, Cuban baseball legend and two-time Olympic gold medalist Lazaro Vargas, left Cuba in 2015.

Other family eventually followed, and now the unit is intact in South Florida.

‘I think they are the most important thing for me,’ says Vargas. ‘Having them on my side, spending time with them, getting figured out that this is just a small window, this year. When you have your loved ones by your side, spending time with them, it makes me feel better.

‘Coming into this year, I just wanted to enjoy the game and it’s been good times out there.’

Dine and mash

He’s not wrong. Even as the White Sox have posted an 18-39 record – a still-ghastly 51-111 pace – the club’s makeup augurs better times. The offseason deal shipping Garrett Crochet to Boston yielded their current leadoff hitter, shortstop Chase Meidroth, and elite catching prospect Kyle Teel, who probably isn’t far away from a promotion.

The future may ride even more heavily on left-handed pitching prospects Noah Schultz and Hagen Smith, each ranked in the top 30 of all prospects. But for now, it’s the young position players hoping to take cues from veterans and set a tone.

On an off night in Baltimore, Meidroth and Vargas went out to dinner, ostensibly a night away from the game. Naturally, they talked hitting.

‘He loves talking about hitting and the game. He’s an awesome guy,’ says Meidroth. ‘It was just a matter of time before he cracked through. He’s an unbelievable hitter, unbelievable player, great teammate.’

And with each passing day, the player with the .889 career minor league OPS gains a little more knowledge on how to stick for good, be it through workshopping his swing or gleaning what he can from the Austin Slaters and Michael A. Taylors populating the clubhouse.

The onramp, finally, is long enough for Vargas’s ample skills.

‘It’s hard to create confidence if you don’t have the success,’ says Barfield. ‘Now you see him go to the plate and it’s like when he was in the minor leagues: He looks like he’s in control of the at-bats, he’s getting pitches and not missing them, where before he was.

‘It doesn’t matter who he’s facing now. He feels like he’s going to have success in every at-bat and you can see that in how he’s carrying himself.’