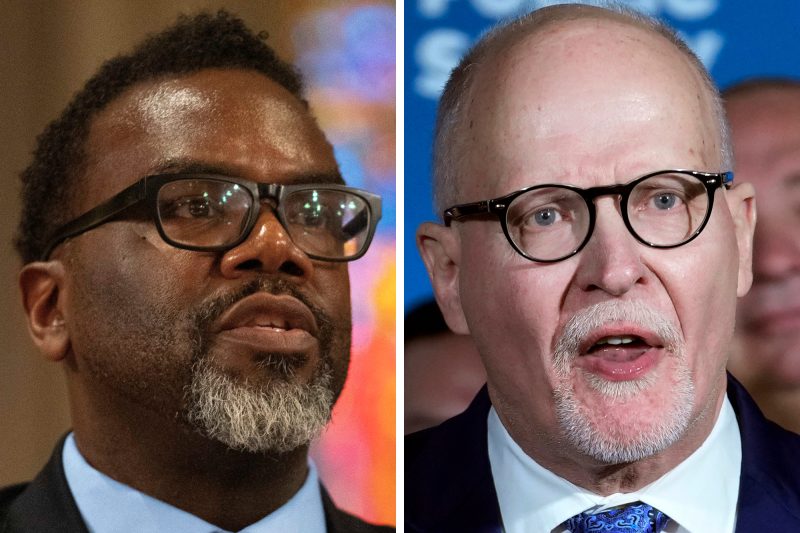

Chicago mayoral candidates have starkly different strategies on crime

CHICAGO — The two candidates in next month’s runoff for Chicago mayor have starkly different visions for how to run the nation’s third-largest city, especially on the issue of crime and policing, the reason that many political observers believe Mayor Lori Lightfoot lost her bid for reelection.

Paul Vallas, a former schools administrator who finished first in last week’s general election, campaigned on a tough law-and-order message, calling for more police officers and cracking down on misdemeanors like retail theft and public nuisance offenses.

Brandon Johnson, a Cook County commissioner, who came in second, energized liberal voters with a message of improving public safety instead by investing in social services, mental health care, education and housing.

Although Chicago faces myriad issues, including a lack of affordable housing, a shrinking number of students in public schools and high vacancies in downtown offices since the pandemic, crime concerns dominated the general election.

In 2021, citywide shootings peaked to levels not seen in a generation as gun violence that had long plagued distressed South and West Side neighborhoods began rising in affluent, predominantly White areas. Crime repeatedly emerged as the top issue in public polls and candidate forums and is expected to remain in the forefront as Johnson and Vallas, both Democrats, spar over the best plan to restore safety ahead of the April 4 runoff election.

Democratic political leaders continue to struggle with perceptions that they are not strong on crime. In addition to fending off criticism from Republicans, Democrats have grappled among themselves over crime and policing in recent elections in other big cities. President Biden and some Democratic members of Congress are also skirmishing over a Republican-led effort to block a D.C. Council bill to overhaul the city’s criminal code.

While Johnson and Vallas have sharp differences on public safety strategies, they agree on one thing: Chicago Police Superintendent David O. Brown was the wrong choice to lead the troubled department and must go.

On Wednesday, he announced that he was leaving.

Lightfoot, who finished third in a field of nine candidates last Tuesday — the first incumbent to lose reelection in 40 years — chose Brown for the job in 2020. Critics and many voters blamed her for the crime rate that rose during her tenure, which began less than a year before the onset of the pandemic and civil unrest over a series of fatal encounters between police and unarmed Black Americans in 2020. During the campaign, she assumed an awkward position between the two leading candidates, attacking Johnson for not supporting police enough while criticizing Vallas for his close ties to the police union.

Lightfoot said in a statement that the next mayor will select a permanent replacement for Brown, who will depart on March 16.

Brown’s resignation puts new urgency on Johnson and Vallas to articulate a vision for who should lead the police force as it grapples with a mix of challenges beyond the crime rate: Officers report plummeting morale and residents harbor lingering mistrust over long-standing complaints of excessive use of force and corruption.

Johnson, 46, is a former public school teacher and union organizer who has called for shifting certain duties for which he says police are not equipped, such as responding to mental health calls, to qualified first responders. He argues that public safety can be more quickly and equitably achieved by shifting vast sums of the police department’s nearly $2 billion budget to policing alternatives, including crisis interventionists, mental health counselors and social workers.

“We’re putting police officers in a space where they are not qualified to address,” Johnson said in a recent appearance on public television station WTTW’s flagship program, “Chicago Tonight.” “We’re forcing police officers to behave as social workers. That’s irresponsible.”

Johnson was the only candidate in the general election who did not explicitly pledge to boost the number of patrol police.

He’s also made his pitch on crime prevention personal, often referencing challenges and concerns he and his wife face raising their children in the Austin neighborhood on the city’s West Side. In 2020, the area had 64 homicides, the fourth-highest by police district.

Following his success in Tuesday’s race, Johnson continued to articulate his argument that more police officers are not the answer while attacking Vallas as an ineffective leader who has left budget disasters in his wake. He called Vallas’s plan to restore the police force to 1990s-era staffing levels unrealistic and misleading.

“When Paul Vallas talks about hiring 1,000 more police officers, where are you going to get those?” Johnson said, arguing it takes about two years for an applicant to become an officer on patrol.

As a Cook County commissioner, Johnson in 2020 sponsored a nonbinding resolution to divert money from police and jails to mental health, housing and job training, and said in an interview that same year that defunding the police was not just a slogan, but a “political goal.” He retreated from the “defund” line on the campaign trail.

Voters who went strongest for Johnson in Monday’s election were from mixed-income White and mixed-Latino neighborhoods on the Northwest and Far North Side that have started to skew more wealthy. He also commanded a sizable voting population in former president Barack Obama’s old stomping grounds on the South Side.

Vallas, 69, is a longtime schools administrator, who ran for mayor in 2019 and finished in ninth-place. He commanded attention early in this year’s race with a relentless focus on law and order, and quickly got the support of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police. That endorsement brought natural voting blocs on the city’s mostly White Northwest and Southwest Sides, historic enclaves for police and firefighters, who are by law required to live inside city limits.

Since emerging at the top of Tuesday’s field, he’s remained focused on distinguishing himself on the issue of crime and touting his experience as a former education administrator.

“I’m offering the type of quality leadership that’s needed,” Vallas said Friday during an appearance on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe.” He said Chicago was facing a “leadership crisis” and called the police department “degraded, demoralized and poorly run.”

Vallas argued the city has never attacked the underlying issues driving crime, which he said were lack of community investment in the poorest parts of the city — a line that hints at how he may appeal to Lightfoot voters, among others.

Vallas has spent most of the past two decades branding himself as a Mr. Fix-It for struggling school districts. In addition to his time running the Chicago public school system from 1995 to 2001, Vallas has worked in the Philadelphia school district when it was on the verge of a state takeover due to poor performance and in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. Throughout his tenure running public schools, Vallas has been a strong supporter of “school choice” and has been criticized for expanding school privatization and charters.

In addition to his 2019 bid for Chicago mayor, Vallas has run unsuccessfully for governor and lieutenant governor.

Vallas had to defend his Democratic credentials after opponents attacked him for receiving campaign contributions from major Republican donors. He also has taken heat for past statements, including an appearance in 2009 on a conservative interview show where he said, “I’m more of a Republican than a Democrat.”

In the five-week sprint to the April 4 runoff, the candidates will vie for the supporters of Lightfoot and Illinois Congressman Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, who won a combined 30 percent of the vote. Lightfoot performed well in predominantly Black neighborhoods, while Garcia dominated in Latino-heavy communities where voters in 2022 made up one-fifth of the electorate.

Neither Lightfoot nor Garcia has yet to say if they’ll endorse either candidate.

Financially, Vallas has outraised Johnson, boasting just over $6 million in contributions in the final days before the general election compared to Johnson’s roughly $3.9 million, according to an analysis of Illinois State Board of Elections data.

Vallas’s biggest financial backers are in private equity, while Johnson’s are from labor groups like the Chicago Teachers Union and the liberal labor coalition United Working Families.

The challenges in Chicago and the racial and social dynamics dominating the race mirror those in other mayoral elections in historically Democratic-led big cities.

In the 2021 New York City race, former police officer Eric Adams (D) beat more liberal primary opponents by promising to be tough-on-crime. In Los Angeles last year, voters embraced Congresswoman Karen Bass (D) over Rick Caruso, a former Republican and billionaire real estate investor who ran to her right on law-and-order.

Crime also is threatening to create a rift between some Democratic members of Congress and Biden, who on Thursday said he would back a GOP-led resolution to block municipal leaders in Washington, D.C., from implementing a major revision of criminal sentencing laws. The predicament forced Biden to weigh the greater political liability: appearing soft on criminal penalties or abandoning Democrat’s long-standing support of D.C. home rule. Although the D.C. Council withdrew the bill on Monday, the Senate is still poised to vote on the resolution.