Hudson Mayes’ coaches try the best they can to describe him in words that can actually describe a 15-year-old kid who is a kind of vintage basketball player.

Hudson is calm. He is selfless. He sees every inch of the court. He takes the charge, makes the extra pass and he likes – no, he loves – that antiquated, midrange jump shot.

Hudson is ‘an old soul,’ a ‘throwback player.’ Those are the words of his coaches, who say the sophomore at Redondo Union High in Redondo Beach, California, is certainly headed for a Division I program. A player, they say, colleges should clamor after, especially programs who want talent, grit and passion. Not hype.

Of course, Hudson can dunk with flashy NBA style. He is 6-4, 185 pounds with muscles starting to bulge on his maturing body. And he can drain those Steph Curry-esque, way-behind-the-three-point-line shots.

But Hudson can’t get away from the midrange jump shot. He laughs a little as he says it. What high school basketball player even thinks about the midrange jump shot?

Hudson does.

There is something magical about the old school basics of basketball, he says. ‘In this day, they don’t really utilize the midrange that much anymore. It’s usually either all the way to the basket or a 3, so I think I’m bringing that back,’ Hudson said. ‘I always grew up learning that.’

Growing up. That is where Hudson’s family legacy comes in, his roots, the people he grew up around – from the time he was a baby in a crib surrounded by plush basketballs instead of stuffed animals. From the time he toted a mini basketball around the living room as a toddler trying time and again to get the ball to fall through that plastic hoop.

‘I was always expected to be a pretty talented player,’ Hudson said from his home in California this month. ‘It’s kind of some big shoes to fill. But I have to. And I’m going to.’

Those shoes belong to Roger Brown, Hudson’s grandfather, one of the greatest Indiana Pacers to take the court. Brown is a Naismith Hall of Famer, a unanimous ABA All-Time Team selection and he was one of the best midrange shooters in basketball in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Brown’s style was smooth as silk and he gladly took the jump shot over a dunk, almost never slamming a ball through the rim in a game, said his former teammate Darnell Hillman.

Brown was quiet, reserved, not flashy or boastful, but he fiercely wanted to win, said George McGinnis, who played with Brown on the Pacers.

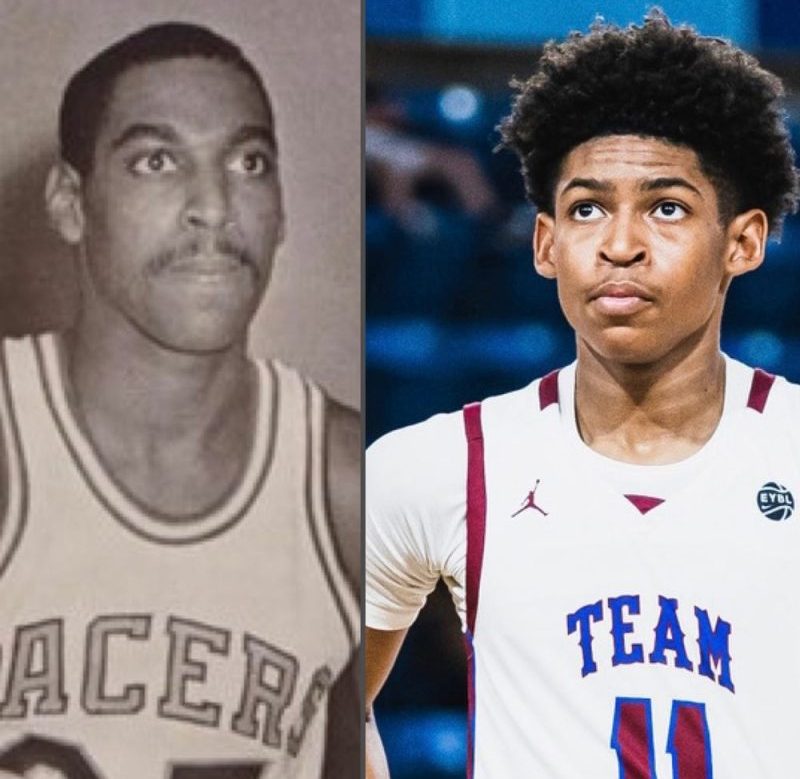

The resemblances on the court between Hudson and his grandfather are uncanny, especially because Brown died in 1997, 10 years before Hudson was born.

‘Even early on, there was just a certain way that he moved that resembled my father,’ said Hudson’s mother Gayle Brown-Mayes, Brown’s daughter. ‘You can’t put your finger on it, but it’s there.’

And nearly 50 years later, as Hudson takes the court crafting his own graceful, sleek moves, those who watch him play say his grandfather, ABA great Roger Brown, lives on.

‘The greatest Pacer ever’

It was 1967 when Brown caught the eye of the Indiana Pacers. He was playing in amateur leagues in Dayton, Ohio, working at General Motors, as the Pacers were forming a team in a new league called the American Basketball Association.

Brown became one of the first players to sign with the team. The Pacers never regretted that.

‘Oh, he was just smooth, just an incredible player, just well skilled at every offensive area,’ said McGinnis. ‘He had that gene where he made every big shot he took.’

The 6-9 Hillman would play the 6-5 Brown every day after practice in a game of one-on-one. Hillman won just twice in two years.

‘Roger could beat two men easily,’ Hillman said, ‘the guy guarding him and whoever is going to pick him up. He was very self-conscious of where he was on the court, who was coming at him and he was very, very good about sharing the basketball.’

Brown, a three-time ABA champion ‘had a special skill for putting people in their proper place — opponents and teammates alike,’ IndyStar wrote in 2020. ‘A burst left, then right, from Brown on the hardwood was like swinging open a set of barn doors on the way to the hoop. Firing a pass at a teammate’s head at an innocuous moment would make certain that in crunch time, they would be ready for anything.’

At Brown’s Hall of fame induction in 2013, Reggie Miller called him, “the greatest Pacer ever.”

‘Hudson’s got some big shoes to fill,’ said Hillman, who has watched Hudson’s video clips. ‘But he’s off to a very good start.’

As Jeannie Brown, Hudson’s grandmother and wife of the late Roger Brown, watches Hudson play she said she sees so many similarities.

‘Roger was always very graceful and so is Hudson. Roger was never harried. Hudson isn’t either. He is always calm, collected when he is on the floor. He knows where everybody is, where he is supposed to be,’ she said. ‘I call him basketball smart. Roger was also. They both know how to make beautiful passes.’

Hudson, whose name is an homage to where he was born by the Hudson River on Riverside Drive in New York City and to his grandpa’s hometown Brooklyn, started showing signs of his sports legacy at a very young age, said his dad Derrick Mayes, an Indianapolis-bred Notre Dame football great and Super Bowl champion with the Packers.

Hudson was 4 when he took to the court in basketball leagues at the Crenshaw YMCA, playing with the older, 5-year-old teams.

Derrick Mayes said he knew his son was going to be special then and he captured it in a video where a tiny Hudson practices a shot and misses.

‘Good shot, alright, let’s try one more,’ Mayes says to Hudson on the video. ‘Make sure you look at the goal right?’ Hudson looks at the goal, makes the basket and then starts dancing.

‘That sums it up. From Day 1, he wanted to learn, he took direction really well, he responded incredibly fast,’ said Mayes. “I knew then, because there is a fine line between being good and being great.’

Around that same age, Hudson said he remembers seeing video clips of his grandfather playing for the first time. ‘I was like, ‘Wow, this is actually my grandpa.’”

Hudson took that legacy and started honing it.

‘We’ve always seen in Hudson his talent, just natural God-given talent,’ said Gayle. ‘He just has always had his head down, always been passionate about it. Coaches were coming to us saying this kid’s got something. We want to coach him.’

‘He’s a horse. He’s not a dog’

Brian Haloossim began coaching Hudson when he was 8 and spent the next five years with him through middle school club ball.

‘Hudson is just really mature. He is an old soul. He is very quiet, but extremely confident. But he is always learning,’ said Haloossim, who has coached high school and was an assistant men’s basketball coach for Division I California State University, Northridge. ‘That is so rare. I remember that was the case from the day I met him, he was just a sponge. He has a lot of raw skills. But he doesn’t rest on that. He works very hard.’

As Hudson’s grandmother, Jeannie Brown has told him, ‘You can have all the talent in the world but if you don’t work at it, that means nothing.’ Hudson has heard those same words, too, from his parents and his paternal grandparents, David and Annie Mayes.

‘I’m a really hard worker. I’m very determined and obsessive so making a certain amount of shots or getting a certain move down, my passion just brings me to work really hard and want to get better,’ Hudson said. ‘So the desire to feel myself getting better and go out and perform the next time and say, ‘OK, I know I did better this time because of all the work I put in,’ that pushes me to go do it again.’

Hudson is always the youngest player on the court, a 15-year-old sophomore, who won’t turn 16 until June. There was never a thought of holding him back, said Derrick Mayes. ‘In fact, I coined the term ‘true freshman’ for him last season in high school,’ he said. ‘We believed in helping him move forward, not holding him back.’

In California basketball circles, Hudson is ‘a known entity’ for many reasons, said Haloossim. He started as a freshman on his high school team and won all-league. In the city championship game, he scored 17 points.

‘That’s pretty unheard of as a freshman,’ Haloossim said. ‘He didn’t do it by being fancy or anything like that. He sort of figured out what coach needed him to do, put up good numbers and stood out.’

Hudson also plays for Team WhyNot, the only Nike EYBL basketball club in Southern California and one of the top EYBL programs on the west coast, sponsored by Russell Westbrook.

‘He’s an aggressive player and he’s confident,’ said Reggie Morris, who is Hudson’s high school and Team WhyNot coach. ‘At his age, he’s big enough and strong enough to get some things done to match his confidence. He plays a brand of basketball that college coaches would lend their eyes to.’

A few D-1 college programs already have their eyes on Hudson, according to his parents.

‘As a former D-1 coach, a lot of my friends are still coaching and I’m telling them to start recruiting him,’ said Haloossim. ‘Coaches that are really looking for the talent and not the hype are going to come after him.’

‘He’s a horse. He’s not a dog,’ said Derrick Mayes. ‘He’s very graceful out there and he plays the game because he loves it.’

This season, Hudson’s high school team went 20-10 and finished second in the league championship. Morris said he figures next season, Redondo Union will be one of the top 10 to 15 programs in the state of California.

‘We have really good, young players,’ Morris said. ‘We can do great things, especially with Hudson leading the way.’

‘We attached immediately’

The story of Hudson on the court today can’t be told without going back to a romance in 1969 between Roger Brown and a dancer and waitress at a night club in Indianapolis.

Brown, along with his Pacers teammates, would come to the club which was owned by a man who had front row Pacers season tickets at the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum. Brown walked into the club one night after a game and locked eyes with Jeannie.

‘We attached immediately,’ said Jeannie Brown, who married Roger in 1977. ‘And that was kind of that.’

Brown and Jeannie started dating and people started talking. Interracial dating in the late 1960s and early 1970s was rare, at least in public. Fewer than 3% of marriages were between interracial couples at the time, compared to more than 20% today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

‘You’d hear a lot of stuff,’ Jeannie said. ‘I just kind of ignored it all.’ All the talk about a white woman and a Black man dating. Jeannie said she never understood the fuss about any of that.

‘Whatever that is, I don’t have it. I’ve never had it my whole life,’ she said. ‘Yeah, I’ve got plenty of faults. Whatever people feel about color and religion, I don’t see those things.’

Jeannie grew up in a diverse neighborhood in Indianapolis. In elementary school, one of her best friends was a Black girl. The corner drug store was owned by Holocaust survivors who had prisoner camp entry numbers tattooed on their arms.

‘They were all just people to me,’ said Jeannie. ‘And so was Roger and I loved him. I loved watching him play.’

The couple had one child, Gayle, who grew up knowing Brown as a wonderful dad, not as some star basketball player.

‘It didn’t really dawn on me when i was younger,’ said Gayle. ‘I was going to old timers games with him. That probably didn’t have the same mystique as somebody that grew up watching him in his prime.’

Still, she said, her father was ‘always kind of bigger than life for me.’ Gayle always wanted to hang out with him and his buddies playing cards. She would sit in a corner and watch her dad with Uncle Mel (Mel Daniels) and Darnell Hillman and all those Pacers greats.

‘And you would see this smile and laugh when he was with those guys you didn’t normally see,’ she said. ‘He was a reserved guy, quiet.’ And a guy who instilled a love of sports in his daughter.

As a young girl and teenager, Gayle was a standout athlete – softball, track, barrel racing, figure skating and beating the boys at BMX bike races. Her dream was to go to UCLA to play softball on a scholarship.

But in high school, after multiple injuries and an ACL surgery, Gayle’s athletic career ended – and she began to forge another path.

Around that time, Oprah Winfrey was doing a model search in Chicago. Thousands of hopefuls entered. Gayle did too and she ended up finishing in the top 10, at 16 years old.

Gayle was quickly scouted by Elite Models and moved to New York City. ‘I never looked back,’ she said.

And as Gayle found success in modeling, a childhood love of hers named Derrick Mayes was setting records at Notre Dame. Their dreams had whisked them away from one another. But that wouldn’t last for long.

First there was football

Derrick and Gayle met in elementary school in Indianapolis. She was in third grade and he was in fourth. By that time, Derrick was football savvy. He had been playing since he was tiny, running through the house with a football in his arm.

‘If I took a liking to it, no matter what it was, my dad made sure that I could go out and experience it,’ Derrick Mayes said.

David Mayes became the president of Fall Creek Little League football so Derrick could play early. He was in second grade running the field with the third graders.

‘He was always outgoing,’ said Derrick’s mom, Annie Mayes. ‘Growing up, he was like a little daredevil. He would try anything.’ But out of everything he tried, Derrick loved football most.

‘I remember we would take him to the high school football games and while the team was playing in the stadium, Derrick was out in a field with friends,’ said David Mayes, ‘playing more football.’

Once at North Central, Derrick began to shine. ‘I started getting a lot of attention the same way Huddy has so there are a lot of parallels and similarities there.’ Derrick’s stellar high school career later landed him in North Central’s hall of fame.

In 1992, it led him to Notre Dame where, as a wide receiver, Derrick set the program record for career touchdown receptions, a feat that was broken by Jeff Samardzija a decade later.

In 1996, Derrick Mayes was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the second round of the NFL Draft. He caught six passes in his rookie season and was part of the Packers’ Super Bowl-winning team. For the next two seasons, Mayes expanded his role with the team and had his best game in 1998, catching three touchdowns against the Carolina Panthers.

Before the 1999 season, Mayes was traded to the Seattle Seahawks where, in his first season, he caught a career-high 62 passes for 829 yards and 10 touchdowns, In 2001, after a 2000 season in which Mayes caught 29 passes and one touchdown, he was cut by Seattle. Mayes was signed by Kansas City in July 2001, but was released during final roster cuts.

That same year, Derrick and Gayle were married. The two had reconnected with Derrick spending his off seasons in New York City.

After football was over, they would eventually move to California and raise their only child, Hudson, instilling a love of school, basketball – and his family legacy.

Grandpa Roger, there are differences, of course

Hudson is 3.8 GPA student with big dreams.

‘I want to go somewhere and get a good education, just honor my legacy and my roots,’ he said. ‘I want to become a businessman and an entrepreneur.

‘When it comes to basketball, the end goal is to play in the NBA, be a really good NBA player, make All-Star teams, win MVPs and go into the hall of fame.’

Just like his grandpa.

There are, of course, plenty of differences between Hudson and Brown. Hillman recently saw a clip of Hudson playing.

‘And I saw him dunking the ball during play,’ Hillman said laughing. ‘And I find that very amusing in that his grandfather would never dunk in warmups or anything – and he could dunk.’ High, soaring two-handed dunks.

McGinnis said Hudson is ‘a little bit more athletic than his grandpa.’ ‘I never saw his grandpa dunk a ball. He was too cool for that. He’d say, ‘You get two points whether you lay it in or dunk it. So Roger chose to just shoot.’

Shoot the layup or, his favorite, that midrange jump shot. ‘I see Hudson doing that midrange, too,’ McGinnis said. ‘I see a lot of similarities. He looks like Roger, too.’

But McGinnis isn’t big on comparisons, mainly for Hudson’s sake.

‘When I’m around Hudson, everybody bombards him with ‘Roger this’ and ‘Roger that,” he said. ‘And I think he appreciates that. He is such a wonderful kid, so polite, he sits there and listens and smiles and says ‘Thank you,’ but you can see it in his face. He wants to live his own legacy. He wants to be his own person.’

Hudson said he is ‘fine’ with people coming up and talking about his grandpa. ‘But I’m also Hudson. I don’t go out on the court as Roger’s grandson.

‘I’m definitely focused on my own path. But I also want to honor him while doing it.’

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.