The crimes Trump could be charged with in Fulton County, Georgia

During a hearing last week involving her investigation of former president Donald Trump and his allies, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis was caught on a hot mic conferring with a fellow prosecutor.

“The future of defendants trump … ” Willis (D) began. But she quickly thought better of that last word, instructing the prosecutor not to use it.

It was a colorful moment. It’s apparent that Willis was using “trump” as a verb rather than a proper noun, but the progression of her investigation suggests that hers could be the first bona fide prosecution involving Trump and others’ efforts to overturn the 2020 election. And we could soon find out whether the phrase “defendant Trump” — this time the proper-noun version — will show up in future legal proceedings.

(Willis’s office has not said whether Trump himself is a “target” of the investigation. Trump’s Georgia-based legal team has suggested that there has been no formal contact between it and prosecutors, reports The Washington Post’s Holly Bailey.)

Willis said charging decisions in the case were “imminent,” while arguing against the release of a special grand jury’s report on her investigation. The question is, what charges could be brought?

According to legal experts, including a group at the Brookings Institution and Georgia State University law professor Clark D. Cunningham, a few could be in play. Below is a look at the various crimes that could be cited, along with the past conduct pointing in that direction and how compelling the publicly available evidence is.

This involves inducing someone else to commit a crime involving an election. There are both felony and misdemeanor versions, depending upon whether the underlying crime is a felony or misdemeanor.

Georgia law makes it a crime “when, with intent that another person engage in conduct constituting a [felony/misdemeanor] under this article, he or she solicits, requests, commands, importunes, or otherwise attempts to cause the other person to engage in such conduct.”

Potential solicitations Trump made include calling Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) and urging him to “find 11,780 votes.” Another is his call to Georgia’s chief election investigator, Frances Watson, in which he urged her to uncover “dishonesty” in her investigation into absentee ballot signatures and assured her, “When the right answer comes out, you’ll be praised.” (Recordings of both calls were published by The Post.)

Others include Trump’s call to Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) to hold a special session to appoint alternate electors, which Kemp said he couldn’t legally do, and Trump’s efforts to enlist alternate — often referred to as “fake” — electors when the state legislature declined to act.

The first two calls might loom the largest. But Trump’s language was characteristically suggestive in those conversations, rather than a direct call to do something specific.

There’s also the question of whether Trump was urging these officials to find fraudulent votes that he had reason to believe didn’t exist. The Jan. 6 committee has presented some evidence that Trump admitted around this time that he lost the election, but Trump’s defense would probably be that he legitimately thought there were fraudulent votes out there. To prove this crime, prosecutors would need to prove Trump intended for the officials to act illegally.

This is related to the above, but it involves working with others to put a plan in motion.

The law states that it’s illegal when someone “conspires or agrees with another to commit a violation of” Georgia election law. Even if election law isn’t ultimately violated, it’s still a crime when there’s “an overt act in furtherance” of a violation.

Whether this charge might apply to Trump’s conduct would depend heavily on what prosecutors determine to be the underlying crime. The potential underlying crimes could include trying to persuade state legislators to overturn the election results, the push for fake electors, or interfering with Raffensperger and Watson in the performance of their election duties, among other actions. A charge of “conspiracy to commit election fraud” could thus involve Trump’s work with lawyers like Rudy Giuliani and John Eastman or with former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows.

Georgia makes it a misdemeanor to “intentionally interfere with, hinder, or delay or attempt to interfere with, hinder, or delay any other person in the performance of any act or duty authorized or imposed by” its election law.

The question would be whether Trump’s suggestions, his potential threats about Raffensperger taking a “big risk,” and conduct such as pushing Watson to speed up her investigation fall under that category.

Georgia law makes it illegal to “tamper with any electors list.”

This law could apply to the fake-electors plot, if prosecutors determine that the intent was to interfere with Georgia’s election process or Congress’s ability to certify the election results. (Some legal experts have suggested that the certificate the fake electors submitted to Congress was itself illegal, because on it, they falsely claimed to be “duly elected.”)

Prosecutors would have to prove that putting forward a list of alternate electors amounted to tampering with the legitimate slate. And even if prosecutors decide to charge this crime, it’s not clear they would charge Trump. There is evidence Trump was broadly involved in the effort, but tying him specifically to Georgia’s fake electors could be difficult. (There is some publicly available evidence that Trump was in touch with one of the fake electors, now-Lt. Gov. Burt Jones, but not necessarily about the fake electors.)

Another potentially relevant law concerns filing false documents. The law makes it a crime to “knowingly alter, conceal, cover up, or create a document and file, enter, or record it in a public record … knowing or having reason to know that such document … contains a materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation.”

This law doesn’t specifically pertain to elections, but could apply to different aspects of the effort to overturn the 2020 result.

Georgia law has a very broad prohibition on making “a false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation … in any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of state government.”

The idea would be that Trump made false statements (to Raffensperger, Watson or others) claiming widespread fraud and that he actually won the election. But the law appears to require that the recipients of such phone calls be in Fulton County, and prosecuting it would again require proving Trump knew his statements were false.

This was previously broached in the case of Giuliani, given his testimony to legislators.

This might be the most intriguing possibility, since it carries some of the stiffest potential penalties of the bunch — between five and 20 years in prison — and would involve proving the existence of an actual criminal enterprise.

Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (or RICO) Act is broader than its federal counterpart. It requires proving two predicate crimes and establishing a pattern of racketeering activity, but it doesn’t require those crimes to be indicted separately. And while such laws are most commonly linked to organized crime, it has been used against public officials.

The predicate crimes could include some of the above, but also other things like influencing witnesses and solicitation of computer trespass (potentially in Coffee County). Not all of the predicate crimes need to have taken place in the county where charges are brought.

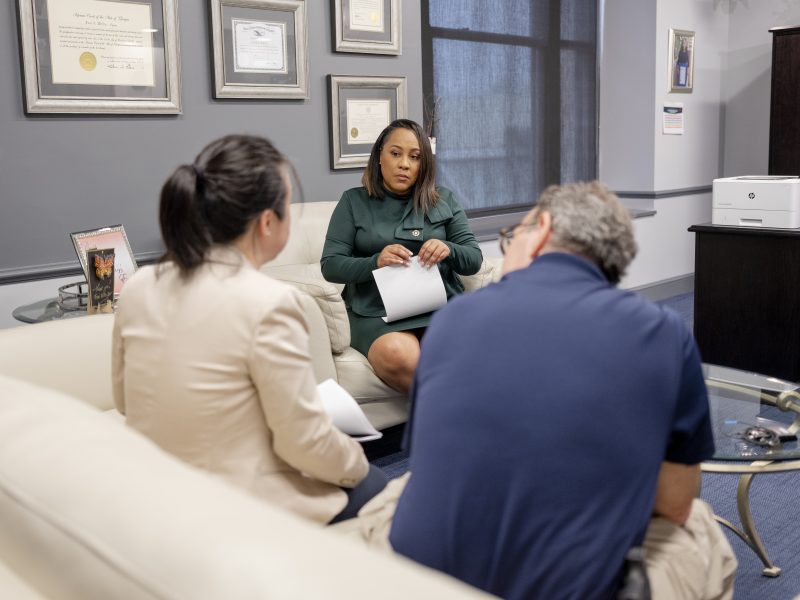

Willis hired a racketeering expert for her team early in her tenure. And she has used the racketeering law extensively during her time as a prosecutor, including against education officials accused of inflating students’ test scores in 2013.

“I have right now more RICO indictments in the last 18 months, 20 months, than were probably done in the last 10 years out of this office,” she recently told The Post.

She praised the law by saying it “allows you to tell jurors the full story,” and that could be attractive in the case of a certain former president.