Georgia Republicans, suddenly losing runoffs, float changing the rules

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) has come out in favor of changing the state’s current runoff system, which requires the top two candidates to run again if nobody gets a majority of the vote.

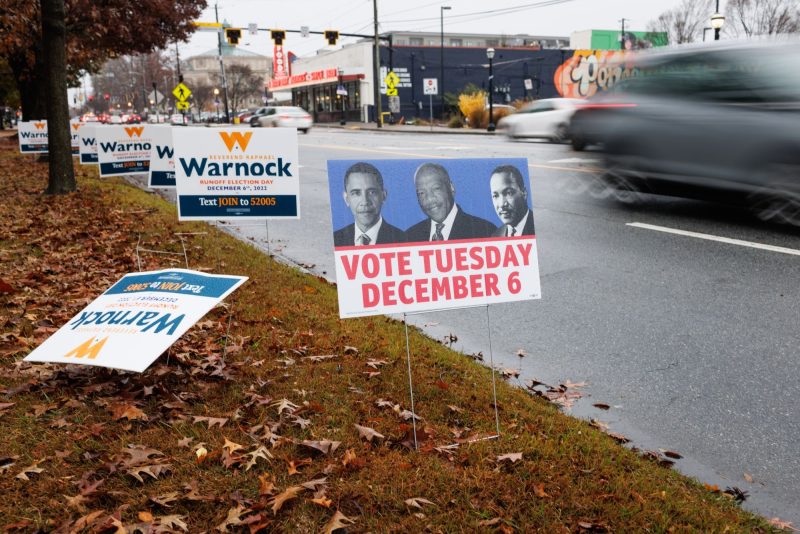

And the timing is certainly conspicuous. That’s because Republicans have just come off yet another loss in a crucial Senate runoff — their third in the past two years.

Would the move obviously advantage the GOP? That’s not clear.

What is evident is that runoffs aren’t as favorable for the GOP as they once were. In 10 Georgia runoffs held between 1992 and 2018, Republicans won nine of 10 races and improved their vote shares in eight of the 10 races. That includes Raffensperger’s own 2018 race, in which he turned a 0.4-point edge on Election Day into a 3.8-point win.

In four of those races, Republicans overturned a deficit. The average shift over that span? In the GOP’s favor by more than five points, on the margin.

The story of the past two years has been very different. Democrats not only won all three Senate runoffs held after the 2020 and 2022 elections, they improved their performances over the general elections in each.

They gained about three points in each 2020 race and nearly two points in the 2022 runoff. In the former cases, they actually took fewer votes than Republicans on Election Day but later won. Democrats also closed the gap in another 2020 runoff, for the Georgia Public Service Commission, by more than two points (though their candidate ultimately lost).

Those are effectively four of the five best runoffs for Georgia Democrats in the last 30 years — and the three most consequential — all in the span of fewer than 24 months.

To be sure, there is a long history of officials changing election rules in ways that, not coincidentally, would seem to benefit their side. As FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley noted recently noted, that applies to the Georgia runoffs themselves.

The runoffs originated as a Jim Crow-era effort by White Georgians to dilute the political power of Black Georgians, as The Washington Post’s Matt Brown wrote recently. They were initially pushed by a segregationist state legislator who blamed his reelection loss on Black voters and later admitted the change was meant to suppress the Black vote.

Democrats lowered the runoff threshold from a majority to 45 percent in the mid-1990s after Sen. Wyche Fowler (D-Ga.) was forced into a runoff and then lost (he would have won outright under the new, lower threshold). Then Republicans took over the state and changed it back to a majority threshold after the lower one enabled Sen. Max Cleland (D-Ga.) to avoid a runoff in 1996 with less than 49 percent of the vote.

Another prominent example this century is Massachusetts Democrats repeatedly changing the state’s rules for Senate vacancies depending upon which party controlled the governor’s mansion and the ability to appoint a senator.

Raffensperger has said his recommendation was motivated by the burden that this system places on election officials, particularly after the GOP-controlled state legislature reduced the runoff period to four weeks after Election Day (runoffs were previously held in January). That placed the runoff right in the middle of the holidays and condensed officials’ work. And runoffs are more frequent now that Georgia is effectively a swing state: There have been six such elections since 2018 — after every major election — compared to eight total between 1992 and 2015.

Among the ideas Raffensperger has floated are expanding early-voting locations, lowering the threshold back down to 45 percent or adopting ranked-choice voting (as states like Alaska and Maine have). The last option is intriguing and would effectively create what advocates call an “instant runoff,” but it would seem to be a hard sell right now with Republicans who are skeptical of the idea — particularly after Trump-oriented Republicans struggled under the new system in Alaska.

Changing the runoff rules would almost certainly be dead on arrival if Republicans were still overperforming in them. But it’s far from certain that Democrats will continue benefiting from them, which might be why some prominent Democrats and civil rights groups appear open to the idea.

Democrats seem to have benefited in the 2020 runoffs because control of the Senate was at stake while President Donald Trump focused on trying to overturn his reelection loss — a move that some (including, sort of, Trump) wagered potentially hurt GOP turnout. And in last week’s runoff, the GOP appeared hamstrung by the flawed candidacy of their nominee, Herschel Walker; he had performed better on Election Day, it seemed, because more popular Republicans like Gov. Brian Kemp (R) were also on the ballot. Those are unusual dynamics that are unlikely to be replicated in future runoffs.

But runoffs do appear to have, at the very least, lost much of their utility for the GOP. Now we’ll see if other Georgia Republicans agree that it’s time to do away with (or reform) them.