Biden scrambles to keep African nations in anti-Russian coalition

With more than 40 African leaders visiting Washington this week, President Biden has a rare opportunity to court a group of nations that have been ambivalent about, and increasingly frustrated by, his global effort to rally support behind Ukraine and mount a unified front against Russia.

Biden this week will host the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, an event last held eight years ago under President Barack Obama. This time, the event comes as the White House is working, with mixed success so far, to coax support from African nations that have been hit especially hard by the consequences of the war in Ukraine, especially a wheat shortage and a disruption in the food supply but also rising fertilizer and fuel prices.

The African Union has condemned Russia’s aggression, but many nations on the continent have otherwise tried to remain neutral because they have long-standing ties with Russia as well as the United States and depend on aid from both, though the United States makes far greater investments. That has played out starkly at the United Nations, where many African countries have declined to vote in favor of U.S.-backed initiatives on Ukraine despite lobbying by the Biden administration.

African leaders have made clear to White House and administration officials that they simply want an end to the war, said a senior administration official familiar with the discussions, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal conversations. The two sides disagree on what tactics to use to get to a settlement, the official said, as the Africans oppose the idea of punishing Russia or insisting that Kyiv must agree to any resolution.

“The Africans want to see a diplomatic solution to this conflict. We generally do, too, but ‘nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine,’” the official said. “The disconnect comes when some of the countries have expressed discomfort with sanctions and critiques of Russia that they think make it more difficult to get to a diplomatic solution.”

Rallying a broad global coalition behind Ukraine ranks among Biden’s top foreign policy achievements, especially now that many European countries are bracing for a cold winter and face a disruption of Russian oil and gas supplies. But African countries have persistently been among the holdouts, arguing that they suffer the some of the worst effects of the conflict and see little benefit in angering Russia.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there had been a slow-building food security crisis in many nations. The United States has long been the largest provider of food assistance globally.

Biden’s courtship of African leaders also unfolds amid a sharpening struggle between the United States and China for influence on the continent. Ahead of this week’s summit, the White House announced Biden’s support for having the African Union join the Group of 20 major world economies, a major step long pushed by African leaders.

Beyond that, the White House has sought to secure Africans’ patience with the anti-Russian effort — or at least prevent them from siding with Moscow — by providing aid for food and other priorities. The summit will include sessions on food security and agriculture, issues that African leaders are eager to discuss. The White House also announced Monday that the United States would commit $55 billion to Africa over the next three years in economic, health and security support.

But it remains unclear how long Biden can maintain the tenuous agreement with African nations as the war nears its 11th month with no end in sight. Biden and other European leaders have made clear they will not force Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky into negotiating with Russia and will let Kyiv decide on the timing and conditions of any talks.

Biden earlier this month said he was prepared to speak with Russian President Vladimir Putin about ending the war but stressed that he had “no immediate plans” to do so because Putin has not shown a willingness to seek a peaceful resolution and has employed brutal tactics against Ukrainian civilians.

“The challenge becomes when [the United States] is asking Africans to take specific sides,’ said Mvemba Dizolele, a senior fellow and director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Africans are saying, ‘We believe there is another way to solve this problem. Global North, United States, Western Europe — sit down with your neighbors and try to bring this to a peaceful resolution.’”

Biden’s expected announcement this week that the United States supports the African Union’s bid to become a permanent member of the G-20 would give African nations a long-sought prize. African leaders have for years expressed frustration at being left out of discussions on global affairs and crises that affect them, including the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

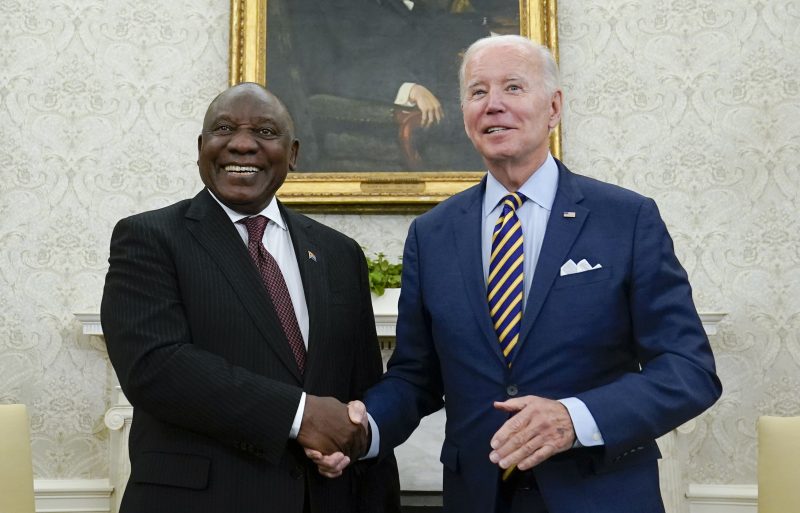

Biden has spoken with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in an effort to combat what the United States sees as misinformation on the continent about the war in Ukraine — including the notion that the food crisis is caused by Western sanctions on Russia — and to try to rally support for the U.S.-led effort. But South Africa, currently the only African nation that is a member of the G-20, remains among the countries that have not supported U.N. resolutions condemning Russia.

There is also a sense of resentment among many nations, Dizolele said, about the amount of money and resources going to Ukraine. The United States has so far committed more than $60 billion, and the administration has requested just under $40 billion in the most recent congressional budget deal, which is still being negotiated. Many Africans feel such resources and attention have never been devoted to their problems, whether the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the civil war in Ethiopia or warfare in the Central African Republic.

Russia’s invasion, meanwhile, affected Africa only indirectly. “They believe while there are global implications, it’s primarily a Western problem, and Africans are used to being told when they have problems, they should find an African solution to their problem,” Dizolele said. “That’s part of the mind-set: Why is it that your problem has to be the entire world’s problem?”

To counter such sentiments, the Biden administration is seeking to emphasize partnership rather than paternalism in its interaction with African countries, officials said, highlighting what the United States can offer amid a deepening worldwide competition for influence with other world powers, chiefly China and Russia.

As Beijing invests billions in African infrastructure projects and Russian-backed paramilitary forces help train African armies, the United States has countered with promises of food assistance and investments in farming and green power.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who launched a new strategy for sub-Saharan Africa during a tour of the region in August shortly after a similar visit by his Russian counterpart, stresses that Washington is not asking African leaders to choose between East and West. But many African countries feel there is an implicit choice.

Ebenezer Obadare, an Africa scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations, said most African nations would have reflexively sided with the United States and its allies if Russia had launched its war in Ukraine a decade ago. But Moscow has stepped up its engagement with the continent, and today, he said, “many African leaders didn’t feel like they had to automatically line up with the West. There are alternatives there.”

While the continent’s leaders appreciate Biden’s decision to hold the first U.S.-African summit since 2014, Dizolele said, they will also be measuring the scale of any aid or investment announcements, and will look to whether Biden commits to holding a subsequent summit or making a presidential visit to the continent.

Dizolele said the impact of the Biden administration’s apparent decision not to hold any formal, scheduled bilateral meetings with visiting leaders — in contrast to the recent state visit by French President Emmanuel Macron, his second in less than five years — will probably depend on the scope of those commitments.

Complicating Biden’s effort further is his stated commitment to put human rights at the core of his foreign policy. Administration officials have occasionally issued public criticism of African countries including Egypt, Rwanda and Ethiopia, and they say they routinely raise these matters in private.

But on other occasions, such as Biden’s recent visit to Egypt, that message has not been readily apparent. Nicole Widdersheim, deputy Washington director for Human Rights Watch, said she did not expect the White House to use the summit to openly criticize African leaders guilty of human rights abuses.

The administration “is going to talk about things they and the African countries mutually care about: democracy, trade, investment, food security,” Widdersheim said. “They’re not going to risk publicly pressing on human rights, because they don’t want to lose influence on the continent to China.”